The following is a transcript of an interview by Oriana Kraft with Dr. Marjorie Jenkins, MD, MEdHP FACP, dean of UofSC School of Medicine Greenville, Chief Academic Office for Prisma Health-Upstate.

The following is a transcript of an interview by Oriana Kraft with Dr. Marjorie Jenkins, MD, MEdHP FACP, dean of UofSC School of Medicine Greenville, Chief Academic Office for Prisma Health-Upstate.

Could you tell me a little bit about how you came to be involved in sex and gender specific medicine?

I became involved in the sex and gender specific medicine movement fairly early on – in 2002. Due to the NIH and the National Centers Of Excellence In Women’s Health programs, data on women’s health beyond just breast and pregnancy and lactation (so-called “bikini medicine) began in earnest in the late ‘90s. The Centers Of Excellence In Women’s Health were grant awarded to provide fund to academic health centers and community-based health centers for them to enhance their women’s health programs by conducting research into women’s health, develop training and educational programs or improve the sex specific clinical care they delivered. The program was defunded in 2005 but the work of the Centers of Excellence really started to get the ball rolling in terms of the collection of research data in both men and women for diseases like Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular disease.

Have we made progress in terms of the research we conduct on women’s health since 2005?

Although more women are participating in clinical research, there are no requirements regarding the reporting of research data by sex and/or gender outcomes in most scientific journals. Even in basic science research, considering every single cell in the human body has a sex, it is still not a requirement in most journals to report the sex of the cells involved in the research studies. There is an NIH policy of Sex as a Biological Variable which was implemented in 2017. This policy required researchers to justify lack of inclusion of both sexes in research, if they are provided funding to research a disease that applies to both sexes and genders. However, this policy falls short in that it does not require analysis and reporting of outcomes by sex.

Although more women are participating in clinical research, there are no requirements regarding the reporting of research data by sex and/or gender outcomes in most scientific journals. Even in basic science research, considering every single cell in the human body has a sex, it is still not a requirement in most journals to report the sex of the cells involved in the research studies. There is an NIH policy of Sex as a Biological Variable which was implemented in 2017. This policy required researchers to justify lack of inclusion of both sexes in research, if they are provided funding to research a disease that applies to both sexes and genders. However, this policy falls short in that it does not require analysis and reporting of outcomes by sex.

What can doctors do to improve the care they deliver to their patients, given the biased nature of the research they are basing a lot of their practices upon?

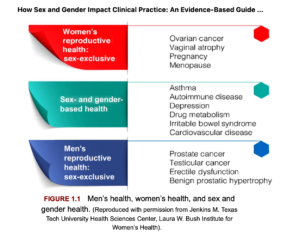

Practicing clinicians need to avail themselves of the clinically relevant sex differences data that is already out there. There is a new textbook on clinically applicable sex differences which I edited with Dr Connie Newman. It is titled How Sex and Gender Impact Clinical Practice: An Evidence-based Guide to Patient Care, published by Elsevier in early 2020. It’s very case-based and applicable to primary care providers. We don’t have all of the answers regarding sex differences, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have a good amount of clinically meaningful data to improve the health of men and women already. Make no mistake: one-sex, gender-blind medicine isn’t just about women. Men are marginalized in some diseases processes and do not receive optimal care as well.

Could you give examples of conditions where men get poor care due to the gendered nature of the care we deliver? I would imagine it happens a lot in diseases like Alzheimer’s or autoimmune disorders…

Not Alzheimer’s. The majority of participants in Alzheimer’s studies are men, even though it eventually becomes a women’s health issue because women live longer with Alzheimer’s and are diagnosed later in life. Here are a few examples of how society often genders health conditions. When an elderly man comes into the emergency room and has fallen down and broken his wrist, emergency physicians will often send the patient home without an order for a scan for osteoporosis. If he fell down just walking across the yard, that’s a fragility fracture, and by definition he has clinical osteoporosis, so normally appropriate follow-up would be to prescribe a bone density scan for osteoporosis. And yet, less than 20% of men seen in the emergency room for fractures actually get the appropriate follow-up they deserve. Yet, men have a much higher likelihood of dying at one year after a fracture than women do. They are also much less likely to return home to independent living. We think of osteoporosis as your grandmother’s disease and this impacts the care men receive. If you look up osteoporosis online, the majority of images you receive are of women. In addition, the majority of bone density scans a located in breast imaging centers which further prevents men from seeking appropriate screening. So, men walk in, see all this information surrounding breast health and breast awareness and are given a pink slip to put on to in order to take the scan The second example where men are marginalized is urinary incontinence. It’s the number two reason why elderly men are institutionalized because their family cannot take care of them. And yet, guess where urinary incontinence pads are located in the neighborhood drug store? Next to the feminine products. This implicit bias dissuades men from purchasing the products they need. It’s all so gendered and marginalizes men’s healthcare.

What about the reverse cases? What is an example, in your opinion, where the healthcare system is missing an opportunity to pursue gendered innovation?

What about the reverse cases? What is an example, in your opinion, where the healthcare system is missing an opportunity to pursue gendered innovation?

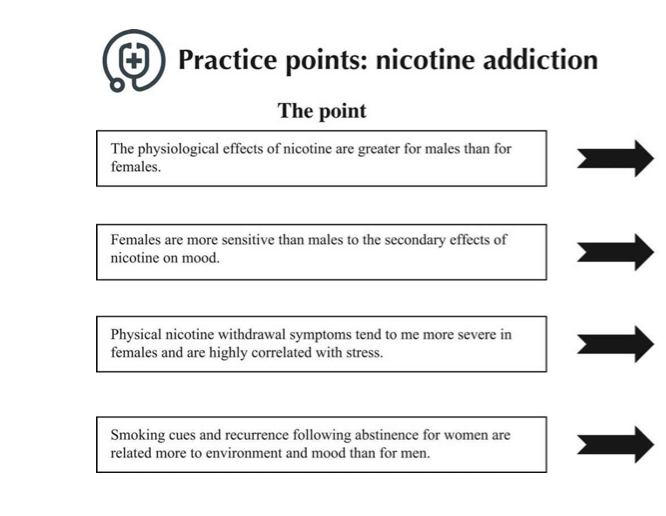

Pharmaceutical companies are definitely missing the boat. Women are much more likely to engage with the healthcare system, take medication and see physicians than men. And yet, the vast majority of medication we commonly use while tested in both sexes do not have the data analyzed by sex. This is much like we discussed in the earlier question. By not testing medication to see if it is more efficacious in women, pharmaceutical companies are losing the opportunity to market to half the global market. This as a real issue. It’s why, when women receive treatment they should ask if the treatment has been adequately studied for safety and efficacy in women. Women need to be their own advocates and begin expecting and demanding personalized treatment. They should ask questions like: “Has this been studied in women? What did the studies show? Is it more or less efficacious? Are there more side-effects?” Roughly 70% of drugs which can be used in women who are pregnant, or lactating have no human data in the drug label. That may seem difficult to believe, but in an audit of over 570 medications, this was born out to be true.

This is Part 2 of a series of Deep Dives on Sex Specific Topics in Medicine, in the aim of connecting students with research being done in the field.

_______________

Gendered practices in medicine are why we need Femtech – to create a space to have conversations around the topic. (And a FemTech Summit like this one of course to assemble chief clinicians, researchers and femtech startups to have the all too important conversation on the areas of women’s health that have gone neglected for far too long). Sign up for the 2022 femtech conference here.

Everything is very open with a precise clarification of the challenges. It was really informative. Your website is useful. Thanks for sharing!